Introduction

Organoids are 3D, miniaturized organs that are generally grown from stem cells (pluripotent or adult) that self-organize in vitro within an extracellular matrix and reproduce enhanced in vivo physiology compared to 2D cell culture. Organoids can be grown from virtually any human or animal organ and signify the next iteration in complexity versus spheroids. Whilst both generate 3D structures comprising multiple cell types, organoids offer greater complexity that, histologically and genetically, better resemble the original organ.

Organoids can be grown from virtually any human or animal organ and signify the next iteration in complexity versus spheroids. Whilst both generate 3D structures comprising multiple cell types, organoids offer greater complexity that, histologically and genetically, better resemble the original organ.

Researchers utilize organoids for a diverse range of applications, including disease modelling, drug discovery and development, personalized medicine, biological therapies and tissue engineering. They provide valuable preclinical insights into how treatments may affect diseased or healthy organs that better inform clinical studies.

Limitations of traditional organoid models

As with any model, organoids have limitations and challenges that surround their use, including:

- Culture longevity/necrotic cores

- Lack vascularization

- Lack immune-component inclusion

- De-differentiation of cells

- Culture variability and organoid homogeneity

- Assay sensitivity

- Depth of data output (organoid pooling is required for higher content outputs)

- Isolated single-organ models

The advances of microphysiological systems

One simple adjustment when using organoids is to switch to perfused cell culture using a microphysiological system (MPS) where a continuous flow of culture medium is applied, mimicking blood flow.

Perfusion serves many functions. As with blood, perfusion provides constant oxygen and nutrients whilst removing waste. This is particularly important for organoid growth and differentiation, as they often suffer from arrested growth and necrotic cores. The removal of this major limitation allows for larger tissues to be produced, which can enable more data-rich analysis.

In addition, microfluidic flow provides vital biomechanical cues. For example, blood flow creates sheer stress, a parallel frictional force within tissues. By introducing the shear stresses of microcirculation into models, it better mimics human physiology and biochemistry. Another critically important aspect of perfusion is cell-to-cell communication. Perfusion induces intercellular movement of the secretome – such as cytokines, proteins and vesicles, thus recreating similar conditions to the human body.

Culturing organoids in perfused conditions using microphysiological systems (MPS), does alleviate limitations, however, their finite longevity still restricts their application, particularly when investigating complex, or latent drug effects. Plus, their relatively small size affects assay sensitivity and the depth of data output. The latter can be overcome by pooling organoids together however, this then increases cost per test.

What do next generation organoids look like?

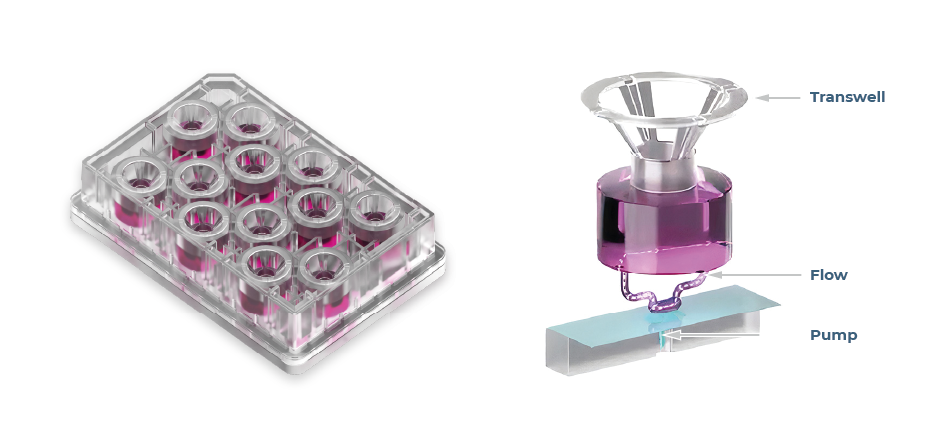

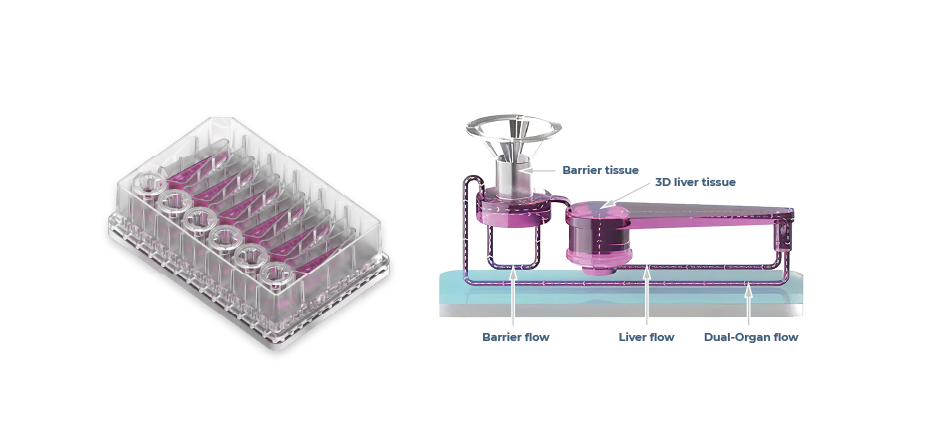

Organ-on-a-chip cultures differ from organoids as they represent three-dimensional tissues with more human-relevant spatial organization. For example, to support microtissue formation some Liver-on-a-chip devices, such as CN Bio’s PhysioMimix Core and Multichip Liver plates, (Figure 1) contain scaffolds with collagen-coated pores.

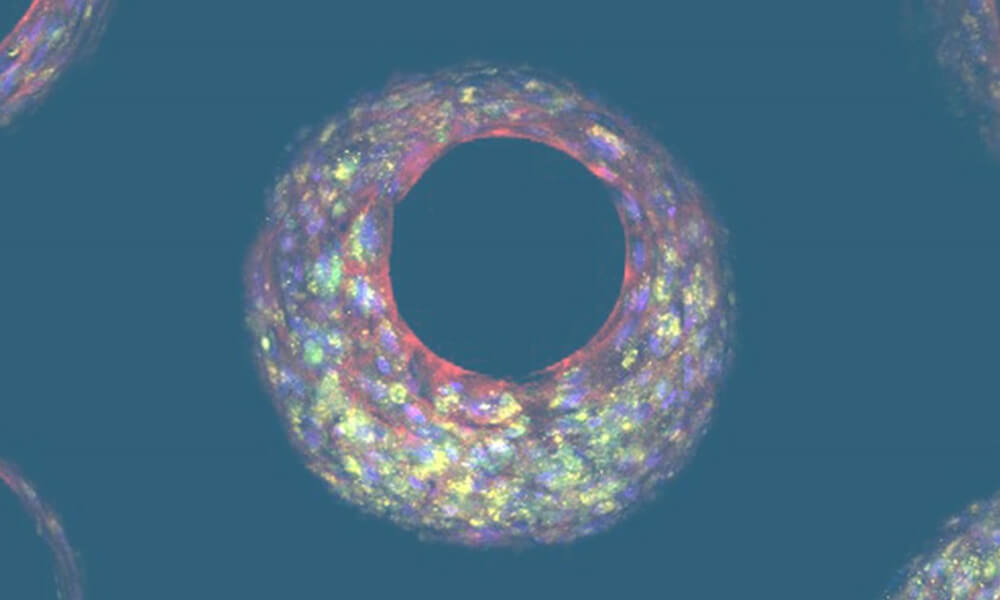

Microtissues form by self-directed assembly from a pre-mix of primary cells and are relatively uniform. Forming within the pores (Figure 2), the microtissues leave an internal lumen through which media can flow, representing the hepatic sinusoid architecture and circumventing necrotic core issues.

Figure 1 – CN Bio’s PhysioMimix Core and Multi-chip Liver-12 plates, with a zoomed in visual demonstrating how perfusion circulates around each chip. A Liver-48 plate containing offering 4x more chips/plate is also available.

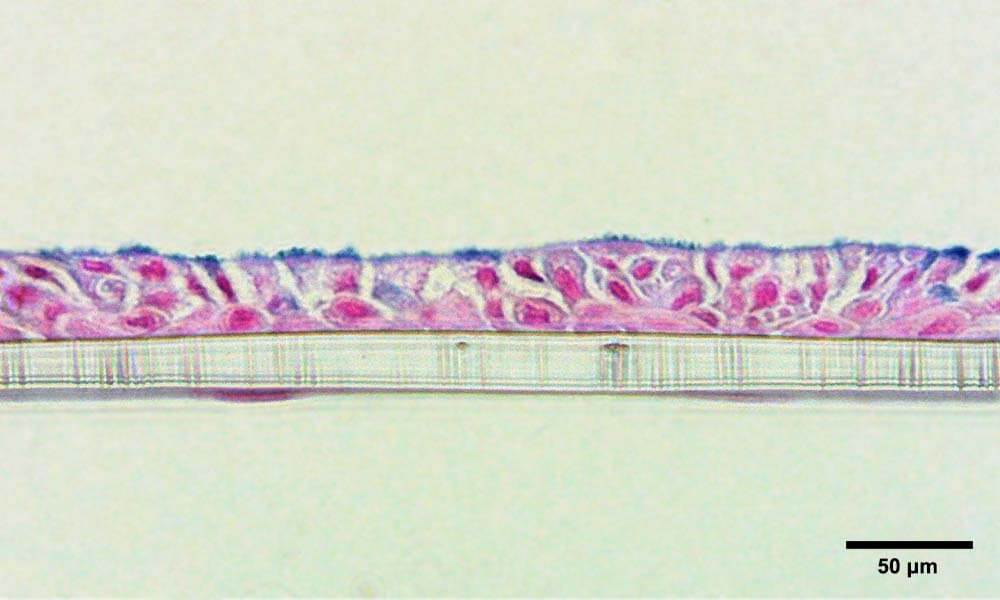

Figure 2: Liver-on-a-chip tissue formed in a pore within a scaffold. Photo credit: Dr Emily Richardson, CN Bio.

OOC cultures exhibit longer-term maintenance of cell health and function for multiple weeks or months facilitated by perfusion, a notable enhancement over conventional organoid cultures, which often lose viability and function in only a few days or weeks1,2. The increased longevity of these models enables investigations into prolonged chronic exposure to drugs alongside long-term studies of more complex biological interactions3.

Physiological relevance is another key obstacle that limits the applications of some organoids, particularly for barrier organs such as the lungs. Architecturally, the lung airway forms a pseudostratified epithelium in which the apical side is subject to the air during breathing. Organoids are commonly cultured submerged in media or gels to enable their formation, so despite apical-in or apical-out lung organoids being developed, they are not subject to the same cues as in vivo. Consequently, organoids have limited use for study areas including infection, environmental research, and drug development, as the main route of entry into the lung – aerosolization and inhalation – cannot occur. Furthermore, key pulmonary functional endpoints such as cilia beat frequency and mucus production cannot be fully understood. Utilizing OOC, (Figure 3). researchers can create more physiologically relevant barrier models (Figure 4), enabling simultaneous epithelial exposure to the air and media perfusion underneath4, 5.

Figure 3 – Multi-chip Barrier plates, with a zoomed in visual demonstrating how perfusion circulates around Transwell® inserts.

Figure 4 – Bronchial lung-on-a-chip tissue after 7 days culture at ALI, with bronchial cells forming a pseudostratified epithelium on the apical side and endothelial cells on the basolateral side of the membrane, respectively. Tissue is stained with Alcian blue to highlight mucus production. Photo credit: Dr Emily Richardson, CN Bio.

The relatively large tissues that OOC generates are highly functional and deliver clinically relevant endpoints, toxicity output biomarkers, and human-relevant metabolism that allow data to be compared to in vivo or clinical scenarios6. These have been notoriously difficult to detect in vitro, but larger-scale organ-on-a-chip microtissues increase assay sensitivity to the point where more sophisticated clinical chemistry outputs can be detected (e.g., aspartate transaminase (AST) and alanine transaminase (ALT)) and more subtle toxicities caused by Phase I and II metabolites7. An interesting study by Nitsche et al., explored the potential of liver microphysiological systems (MPS) of varied configurations to model cholestatic chemical effects. Their findings highlighted that Bile acid synthesis was detectable but of low magnitude in perfused organoid culture, however, the cultures failed to replicate cholestatic injury biomarkers when test compounds were applied. By comparison, primary human hepatocyte liver-on-a-chip microtissues (cultured by a PhysioMimix MPS), responded to all three test compounds reporting decreased bile acid release, a biomarker of cholestatic injury8.

In addition, larger microtissue cultures enable deeper mechanistic insights to be gleaned from each tissue (rather than organoid pooling) including soluble cell health and functional markers, as well as mining tissues for data-rich endpoints such as high-content imaging and -omics assays9, 10.

Furthermore, it is possible to add further human relevance to OOC-based assays by fluidically interlinking organ models. For example, connecting liver tissues with another “route of entry” organ (gut or lung, Figure 5) enables the study of reactive metabolite-driven toxicity as well as the evaluation of drug absorption, metabolism11, and importantly bioavailability12.

Figure 5 – Multi-chip Dual-organ plates, with a zoomed in visual demonstrating how perfusion circulates around barrier and liver compartments.

Immunocompetence, which is another key limitation of organoids, can also be incorporated into OOC through the culture of tissue-resident and peripheral immune cells into OOC, the latter of which are circulated by media perfusion. The recapitulation of the immune system allows scientists to uncover immune-mediated toxicity issues, induce common disorders that have an inflammatory element, such as Metabolic dysfunction-associated liver disease (MASH6), or to model human responses to infection, such as COVID-195 or Hepatitis B2 where animal use is less suited.

Conclusion and recommendations

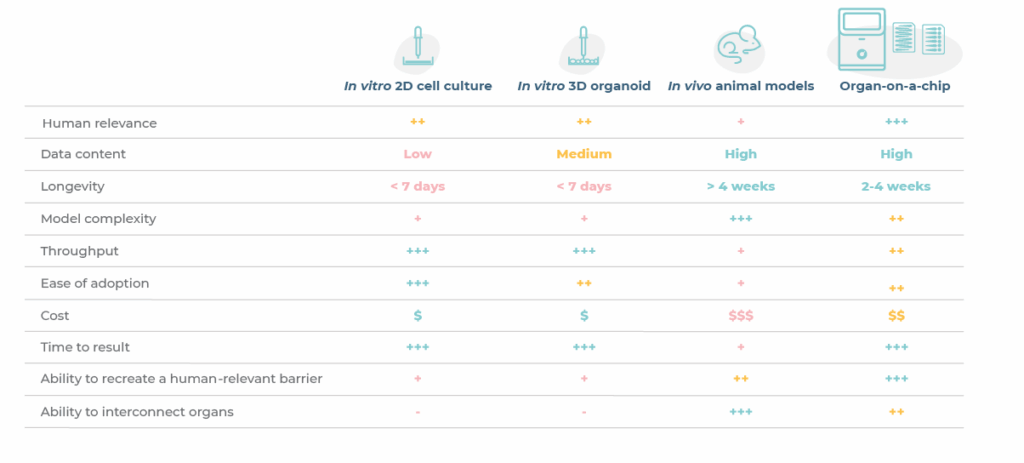

To conclude, organoids are powerful in vitro tool that have enabled researchers to enhance the human-relevance of drug discovery and development workflows over traditional 2D assays and animal models (Table 1). However, their limitations have paved the way for more complex cell cultures like OOC that more accurately recapitulate key aspects of human physiology.

Supplementing organoid use with OOC provides the means to further advance workflows by unlocking the ability to detect deeper mechanistic insights, more complex and latent effects that may otherwise be missed. Collectively, these approaches provide a path forward to circumvent the inter-species limitations of animal models to bridge the gap between preclinical and clinical data, whilst also supporting regulatory momentum to reduce and replace animal use in drug development.

Featured resource

References:

- Rubiano et al., Characterizing the reproducibility in using a liver microphysiological system for assaying drug toxicity, metabolism, and accumulation. Clin Transl Sci, 2021.

- Ortega-Prieto et al., 3D microfluidic liver cultures as a physiological preclinical tool for hepatitis B virus infection. Nat Commun, 2018.

- Long et al., Modeling therapeutic antibody small molecule drug-drug interactions using a three-dimensional perfusable liver coculture platform. Drug Metab Dispos, 2016.

- Phan et al., Advanced pathophysiology mimicking lung models for accelerated drug discovery, Biomat Res. 2023.

- Caygill et al., Dynamic Culture Improves the Predictive Power of Bronchial and Alveolar Airway Models of SARS-CoV-2 Infection bioRxiv, 2025.

- Kostrzewski et al., A microphysiological system for studying nonalcoholic steatohepatitis. Hepatol Commun., 2019.

- Rowe et al., Perfused human hepatocyte microtissues identify reactive metabolite-forming and mitochondria-perturbing hepatotoxins. Tox In Vitro, 2018.

- Nitsche et al., Exploring the potential of liver microphysiological systems of varied configurations to model cholestatic chemical effects. Arch Toxicol (2025).

- Gallager et al., Normalization of organ-on-a-Chip samples for mass spectrometry based proteomics and metabolomics via Dansylation-based assay. Tox In Vitro, 2023.

- Novac et al., Human liver microphysiological system for assessing drug-induced liver toxicity in vitro. JoVE, 2022.

- Milani et al., Application of a gut-liver-on-a-chip device and mechanistic modelling to the quantitative in vitro pharmacokinetic study of mycophenolate mofetil. Lab Chip, 2022.

- Abbas et al., A primary human Gut/Liver microphysiological system to estimate human oral bioavailability. Drug Metab Dispos, 2025.