Different types of Drug-induced Liver Injury (DILI)

Drug-induced liver injury (DILI) is a longstanding and significant problem for clinicians, pharmaceutical companies, and regulatory bodies. Broadly, DILI refers to adverse reactions to a drug that can lead to serious liver damage and, in the most severe cases, organ failure and death. Historically, these adverse reactions can be separated into two sub-categories:

- Intrinsic DILI: The drug or drug metabolite induces liver toxicity in a predictable and dose-related manner. Most individuals are affected at some dose, and the toxicity is generally consistent across species. Hepatotoxicity occurs within days, and pathophysiology is similar across incidences.

- Idiosyncratic DILI: Drug-induced hepatotoxicity in this category is, traditionally, unpredictable and does not appear to correlate with dosing. Onset is also quite variable and can range from days to weeks to months. The presenting pathophysiology and mechanism of toxicity will vary between individuals and furthermore, only a small subset of exposed individuals will experience these adverse effects. Potentially most concerning, however, is that this type of DILI is generally not consistent across species.

It is well known that most drug candidates fail at some point in the development pipeline, and DILI is the most frequent cause of FDA warnings and drug withdrawal from the market. While failure is an unavoidable part of the process, it is significantly better for those drugs to fail early, before adverse reactions appear in humans (whether that be in clinical trials or after widespread release). Failing early is advantageous because it reduces the amount of investment in a failed project, limits negative market fallout due to loss of public trust, and circumvents ethical dilemmas concerning human trials. While intrinsic DILI should be picked up in preclinical models and, at worst, the earliest stages of clinical trials, idiosyncratic DILI often goes undetected until Phase III/IV. This is largely because:

- Premarketing clinical trials are underpowered, making them unable to observe idiosyncratic DILI in the small subset of individuals it would occur in and

- idiosyncratic DILI seems to be species-specific, so preclinical models often fail to capture human toxicity.

Appropriately, idiosyncratic DILI has been a focal point of pharma research in recent years in an attempt to predict the unpredictable. An increased understanding has led idiosyncratic DILI to be subcategorized further; however, in order to keep this post succinct and digestible, we will focus on immune-mediated toxicity, specifically immune-mediated DILI. The following review article is a good place to start if you are interested in the other categories of idiosyncratic DILI. Additionally, for a more general overview of DILI, the challenges it presents, and upcoming solutions, please check out my previous blog about de-risking the DILI process.

In vivo approaches struggle to recapitulate the immune component

While the boundaries of classification are still being debated, immune-mediated DILI generally refers to a drug-induced immune response against the liver that results in organ damage. Acetaminophen is a prototypical example of intrinsic DILI – liver metabolism generates a reactive species that, when over-accumulated (such as during an overdose), causes mitochondrial damage and hepatocyte necrosis. However, it is important to note this acute liver injury can then lead to subsequent damage from an immune response due to the release of danger-associated cytokines from the necrotic cells. When talking about immune-mediated DILI, we focus on DILI that results from an adverse immune response in the absence of predictable drug-induced hepatotoxicity.

Animal in vivo models of intrinsic DILI are generally straightforward: a large enough dose of hepatotoxic compounds will lead to liver damage in most animals. Even so, there are still caveats and complications which reduce the translational relevance of these models. For instance, with acetaminophen, hepatotoxicity in mice resembles what is observed in humans, but rats are far more resistant and require a substantially different dosing regimen to induce the same toxicity.

As expected, in vivo models’ ability to predict immune-mediated DILI is much less clear. This is largely due to the unique complexity of the human immune system, many aspects of which are not naturally recapitulated in other animals. For instance, trovafloxacin and diclofenac, two well-known drugs with immune-mediated DILI risk, do not induce DILI in mouse models. To address this, mice are often pre-, co-, or post-treated with inflammagens (e.g., lipopolysaccharide) to artificially activate an immune response in the presence of the drug. While this can indeed induce a DILI phenotype, its human relevance is questionable for a number of reasons, but, mainly, the observed toxicity is neutrophil-mediated, which is not the typical pathophysiology for human immune-mediated DILI.

The underlying mechanism causing the significant species-dependent disparity in DILI for the above is still being investigated; however, there are drugs with human-specific imDILI whose mechanisms are somewhat better understood. Lumiracoxib and ximelagatran, both of which were pulled from the market by the FDA after liver damage was observed in a small subset of patients, have been shown to instigate an adverse immune response by interacting with specific isotypes of human leukocyte antigens (HLAs), cell-surface proteins that regulate immune-mediated cell destruction. Importantly, the HLA complex is uniquely human; while animals have a comparable system called the major histocompatibility complex, they are far from identical. In order to observe immune-mediated DILI in animals, they must be genetically modified to express the HLA isotypes of interest. Doing so not only dramatically increases the cost of the in vivo model but also requires previous knowledge of which HLAs (a class that includes many) are of interest.

Animal models have been helpful in screening for intrinsic DILI and have provided valuable information, but, ultimately, they are unable to recapitulate the uniquely human immune microenvironment, a fact that is highlighted by their often-contradictory results when it comes to the mechanisms of idiosyncratic DILI. Additionally, the inherent complexity of whole animal studies makes it difficult to parse out what is and is not translatable to the clinic.

Do new drug modalities complicate the situation?

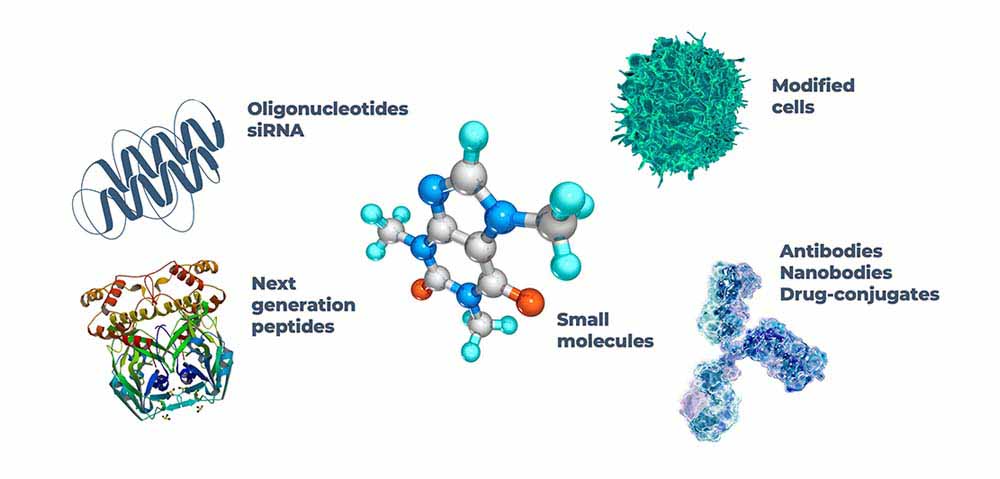

It is also important to evaluate how effective our current models are as drug development expands beyond the realm of small molecules. Chemically synthesized and well-characterized, small molecules often exert their influence on very specific cellular processes. On the other hand, newer modalities, such as ‘biologics,’ can vary considerably in size and composition and work on a broader scale. Of particular importance, newer modalities are often tailored specifically to humans. The liver of a mouse is homologous to that of a human; there are differences, but many of the enzymatic mechanisms involved in metabolism are “like enough” to be affected by small molecules in comparable ways. In contrast, a therapeutic antibody targeted specifically for a human protein will likely experience poor target-binding in a mouse model. Gene-based drugs are no exception since antisense oligonucleotides (ASOs), and small-interfering RNA (siRNA) modulate gene expression by binding specific RNA sequences.

Some preclinical trials of these new modalities utilize non-human in vivo models under the assumption that the general pharmacokinetic profile and, therefore, toxicity is independent of species despite the target being human-specific. For example, mouse, rat, and monkey models were used for toxicological studies of the ASO drug mipomersen. Minimal increases in hepatotoxic markers led to FDA approval in 2013 with a block box warning for the risk of hepatoxicity; however, the drug was pulled from the market in 2019 due to these dangers.

Genetically engineered animals are one approach to including human-specific components in preclinical in vivo trials (as mentioned above). Computer modeling has also been employed for gene-based therapeutics in an attempt to predict potential adverse effects based on an individual’s unique genetic sequence. While helpful, these approaches require previous knowledge of how these adverse reactions come about and neither aid in predicting the unpredictable. Ideally, alternative models using human cells with adjustable complexity to allow for greater granularity when investigating cell-cell interactions would be employed to complement and/or replace in vivo results.

Traditional in vitro approaches have their own limitations

The answer to using human cells without endangering human lives lies in in vitro models. Many drug development pipelines already employ human in vitro models in their preclinical studies, so why are drugs with a significant risk of immune-mediated DILI still being missed? The answer lies in the ‘adjustable complexity’ written above. Common in vitro screening methods involve hepatocyte cell lines seeded into 2D culture plates. There are three areas of improvement that are vital to building more predictive in vitro platforms.

- Cell Source: Primary hepatocytes are considered the gold standard for human-relevant liver models and are only limited by their unstable differentiation in 2D. Immortalized cell lines derived from hepatocellular carcinomas are easier to obtain and yield a more stable phenotype. However, due to their divergent genetics and reduced hepatocyte functionality, they are often unsuitable for imDILI assays. On top of this, as imDILI only occurs in a subset of the population, multiple donors with diverse genetics are required for reliable detection.

- Microenvironment: Autocrine, paracine, and juxtacrine communication, along with signals from the extracellular matrix are all essential in creating an in vitro liver tissue with functionality comparable to the in vivo organ. While you can reproduce the molecular inputs of these different cues in a 2D culture plate by adding cytokines exogenously or coating tissue culture plastic with an ECM, a 3D culture is required to recapitulate the exceptionally important spatial and temporal aspects of these signals.

- Co-cultures: Although it is important to use relevant cells and culture them in an appropriately 3D environment, it is difficult to model immune-mediate DILI without an immune component. As such, parts of the innate (e.g. Kupffer cells) and/or adaptive (e.g. T-cells) immune systems must be included in in vitro imDILI screening.

Incorporating all these improvements will require the adoption of new platforms in place of the standard 2D culture plate. Indeed, growing primary liver cells in 3D not only increases the culture’s sensitivity for hepatotoxic compounds, it also significantly increases the longevity of the cells, allowing for longer and repeat dosing regimens that more closely resemble what is seen in the clinic.

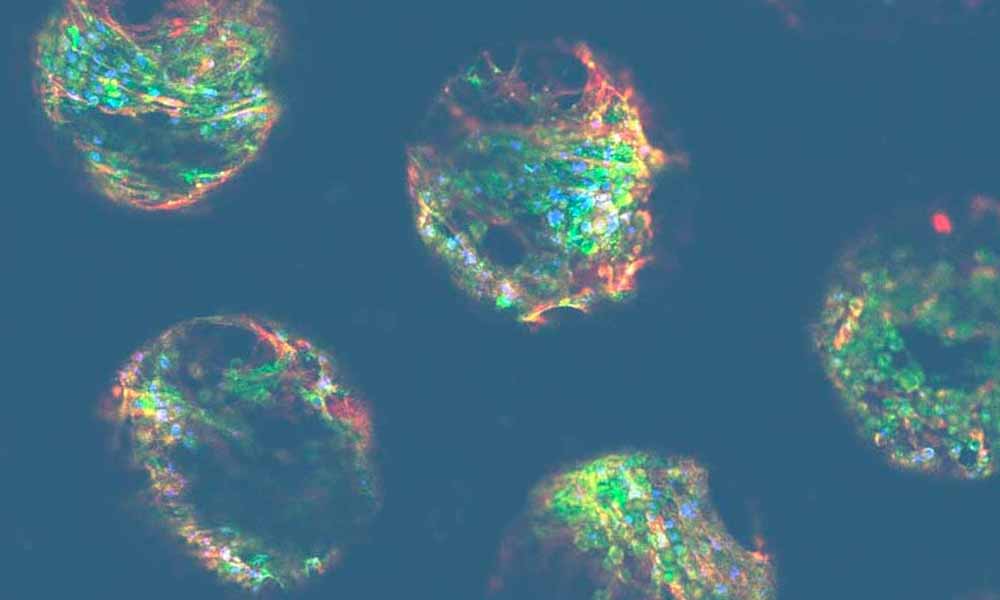

In recent years, 3D methodologies have been utilized to generate hepatocyte cellular spheroids. These small, round clusters of cells form via self-assembly and display a functional morphology closer to in vivo than its 2D counterpart. However, while an improvement, these types of cultures are still limited by their static environment. The liver is a highly vascularized organ with exceptionally metabolically active hepatocytes; active cell culture perfusion is required to mimic the hepatic physiochemical environment adequately.

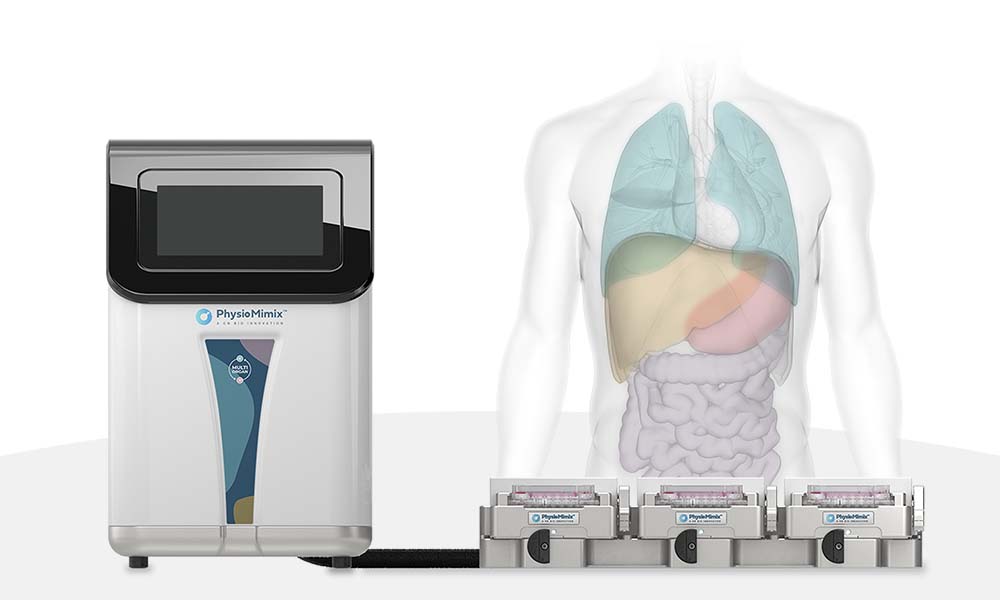

Immune-competent organ-on-a-chip platforms address these issues

Microphysiological systems (MPS) are organ-on-a-chip platforms that utilize active pumping to deliver biologically-relevant perfusion throughout cell culture. Acting as the in vitro equivalent to vascularization, MPS liver models provide vital biomechanical cues while balancing nutrient delivery and waste removal for the active hepatocytes. Not only do these models exhibit increased functionality and longevity compared to other 3D platforms, like spheroids, but they have also been shown to be even more sensitive to hepatotoxic agents.

As discussed throughout this post, one of the most important factors dictating the predictability of an imDILI model is the inclusion of a human immune component. While the innate immune system can be simulated by including nonparenchymal cells, such as Kupffers, into the cell seeding of the microtissue, recapitulating the adaptive immune component has proven difficult in static 3D liver models. With a perfused culture system, human peripheral blood mononuclear cells (or other adaptive immune cell types) can be added to the media, which is circulated through the culture, recreating how these cells would circulate through the body in vivo.

The addition of the perfusion and human immune components, combined with the ease of sample access inherent to in vitro models, also means MPS models are relatively agnostic to drug modality. Bolus dosing of large biologics and oligonucleotides in static culture often yields a diffusion gradient within the cell’s microenvironment, a poor representation of how exposure would occur clinically.

The development of these MPS models has taken us into a new age of drug discovery to predict what has traditionally been thought of as unpredictable. As more and more commercial OOC models become available, selecting the right platform for your needs is important. The PhysioMimix® OOC range of MPS offers an open-well solution that allows for easy drug dosing and cell monitoring while also being accessible to the average cell culture scientist. This is exemplified in an online video of the PhysioMimix DILI assay published in Jove, which can be accessed here.

Embedded 3D scaffolds and media perfusion ensure hepatocyte functionality, while the open-plate architecture of PhysioMimix makes it simple to add other cell types as required to capture adverse drug responses. Furthermore, the PhysioMimix DILI assay has been characterized extensively and shown to produce reliable, robust data with both small molecules and new modalities – you can read more in our latest Application Note here.

For more information about CN Bio’s PhysioMimix OOC range of MPS click here

To learn more about the PhysioMimix Immune-mediated DILI Assay click here